Kevin Walz is a self-proclaimed risk taker.

Regarded by the design community as an artist, inventor, and visionary, the 1994 Interior Design Hall of Fame Inductee's range of influence spans across sectors of the design world to include, interior, industrial design, and product design.

Having long established his company Walzworkinc between New York and Rome, Walz has developed longstanding collaborative relationships with companies such as Ralph Pucci, Tufenkian, Design Within Reach and Wolf Gordon. Upon his recent return to New York City from Rome, I was lucky to spend an afternoon over a warm cup of tea with him. We talked about coming up in New York before "loft living," the tug of war between design and architecture, and the life of a studio practice.

Walz describes his introduction to interior design as "walking in on a moving train." The newlywed couple had begun construction on their own home, pulling together resources and know-how to make their newly acquired loft home. "I started renovating it, before I knew how to do any of it. I had a friend that was an artist, that was making cabinets - he became my contractor." By word of mouth, he earned three projects - all designing homes, designing lofts before the notion of "loft living" became stylish. "This fashion designer walked in and asked how I knew how to do this, then she said she was firing her architects. This happened again and the second time, I decided not to say that I didn't know what I was doing."

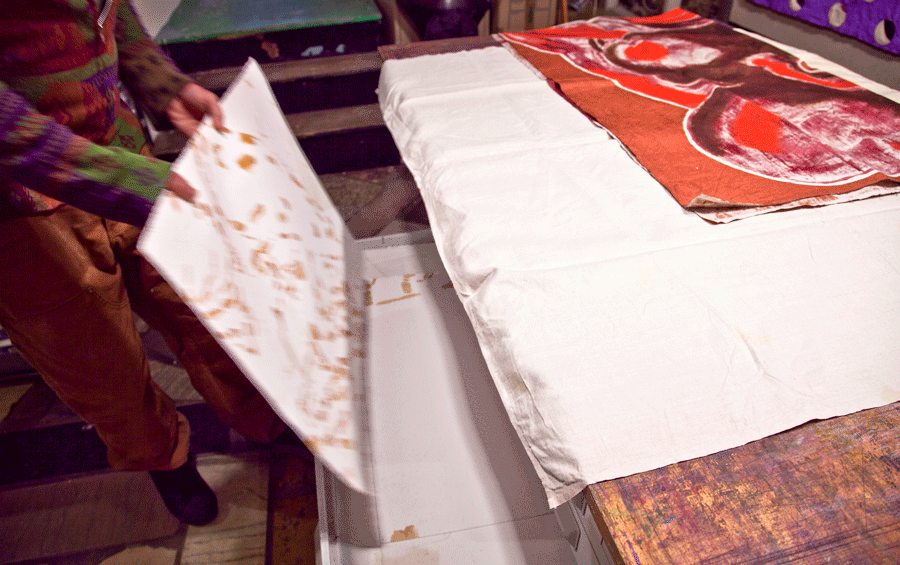

We descend the staircase to the basement of the building, where Kevin has built out a studio. A series of paintings on fabric are tacked evenly spaced along a homosoate wall.

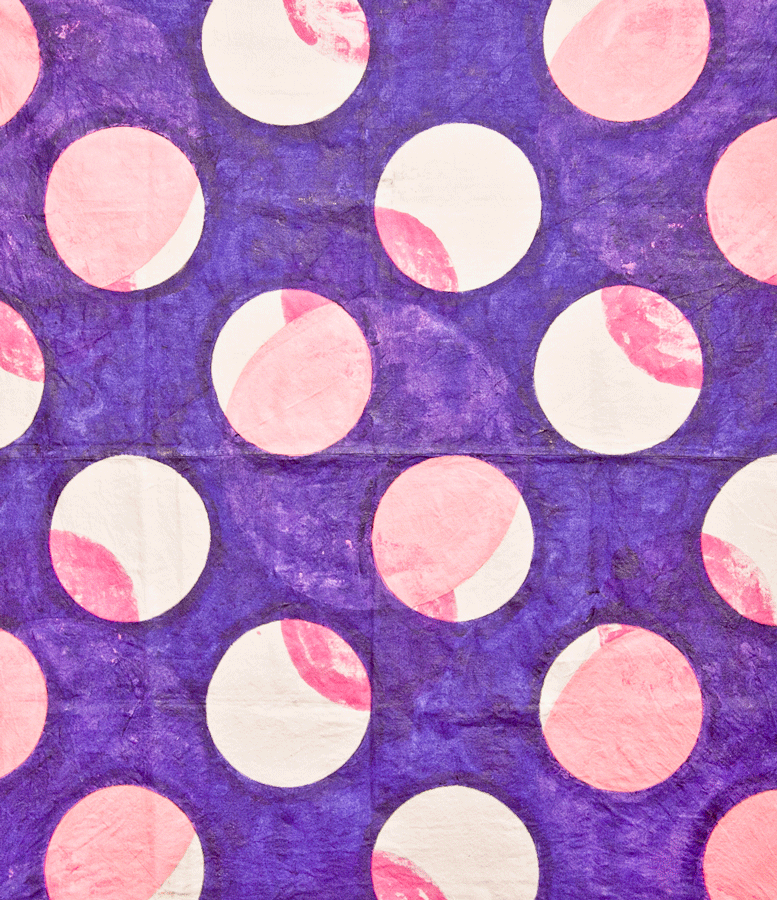

"These are paintings that are painted on one side but must be shown double sided, not on a wall but hanging. One side is painted and becomes an underpainting for the other side." Waltz walks me through the pieces, lifting one to reveal a circular pattern traced onto mylar. The pattern, previously rejected textile for Wolf Gordon, is repurposed as a series of paintings. Nearby, a pair of chairs face each other, feeling more like a Bauhaus drawing than a space for seating. Walz's work makes frequent lateral movements from one discipline to another.

Kevin Walz made New York home a long time ago. His stories describe an early approach to life experience that feels intuited and self aware. Starting out as a visual artist, between Pratt Institute and the New York Studio School, Walz recalls his memories of New York in the mid 70s, "The best thing that happened to me while at Pratt was meeting my wife who I coincidentally ended up with in the elevator four times. We moved into a small apartment in Tribeca, then named Washington Market. There was a freight elevator and a former freezer that was my wife's darkroom. She wore knee high galoshes to develop her photos. She became tired of all the rats scurrying around her feet while she worked. So we moved to a loft on 20th street - at the time, we bought it for $26,000. It was a 4,000 sq ft loft, and it's where we worked"

Entering Kevin Walz's living space is something like walking into a cross between a design studio and showroom. Prototypes and his newly produced designs for chairs and lighting fixtures are installed in his living space next to pieces he designed over the span of his career. They evolve as functionally efficient objects because they are lived with, perceived throughout a day and in a working home. A new wallpaper for Wolf Gordon that "has a black underpainting and is painted on top so that there is some movement on the wall, rather than a wallpaper than stands still." A rug inspired by Yves Klein blue. A featherweight, elegantly silhouetted chair that he designed with his brother, a boat maker. The table we stand over displays a series of prototype finishes for a new lighting fixture that is also mounted into the ceiling. He shows me his favorite, nickel plated brass, pointing to details in the reflection of light and its formal construction. The fabricator created the piece from spun aluminum, to eliminate the evidence of a welded line around the perimeter of the disk shaped object. These pieces all exist in his home - constantly worked through and reconsidered before they are approved for production.

Viewing his pieces reveals an attention to the experience of space, front and back, painting under and onto. Objects feel like drawings. Paintings are considered three dimensionally. In Walz's studio, some ideas remain drawings, while others move onto becoming color ways, or evolve into functional objects.

Upon asking him the impetus for his return from Rome, Walz says, "When I went to Rome it was really a cutting off of my life and how I did things. So when I moved back it was about starting my life for another time. And it all happened in one day. It was a day in July, a year ago 2013, and I went to my studio…I realized that I had completed the second chapter in my adult life, and I was ready to begin my third. I thought , the two most important people [his daughters] live overseas..

I started thinking 'how do I want this to be?' I decided I don't want anyone working for me. I want to make things myself. Anything I do, I want to make basically on my own. "

Soon thereafter, he had two teaching positions at both Pratt and Parsons in design studio and color theory. Not unlike his approach to design, Walz's approach to teaching relies heavily on the act of seeing.

"I have an exercise that I do with my students in my color class at Pratt. But they are more like tricks. I have them select something from nature, and then pick the colors that are affiliated with it. One student picked an apricot - and couldn't figure out the colors. Because it's impossible ! Colors from nature are impossible to simply match up with Color-Aid. I always say to students, you can't talk about color without talking about texture and material. The way light moves, changes color. The whole idea that Joseph Albers is the example for color [in design school] is nonsense. If his work was about depicting an actual space, none of those colors would be possible.

I have no problem with the color white - it's just that people often assume that white makes a space bigger. In reality, white only sets scale for a space. It measures. I tell my students not to rely on what is predetermined. "

When asked about the recognition of designers for critical perspectives on space, Walz explains, " There are no identified visionaries in interior design. The visionaries that have actually been celebrated as great designers are really architects. Interior design hasn't found it's visionaries yet. Architects aren't taught the sensitivity required to really understand interior space. They aren't taught about color, interior materials. Yet they are constantly recognized for spaces they design." To Walz, the intermingling of interior design with the art world is an easier exchange .

"Back then it was impossible for a designer to be taken seriously as an artist. Now you have galleries like Gagosian doing shows with designers like Marc Newson. Salon 94 is doing it now with Betty Woodman. The artworld is embracing it more because galleries are realizing that once they find a painting for a client's wall, well the client may also want something functional. Look at Julian Schnabel. Times are changing."

Kevin Walz creates things that are both timeless and of their time. While the overlaps between artist and designer appear to homogenize the two, the limits of each discipline keep them within their respective spaces.

Walz's solution: be the common denominator.